Mini Les Paul

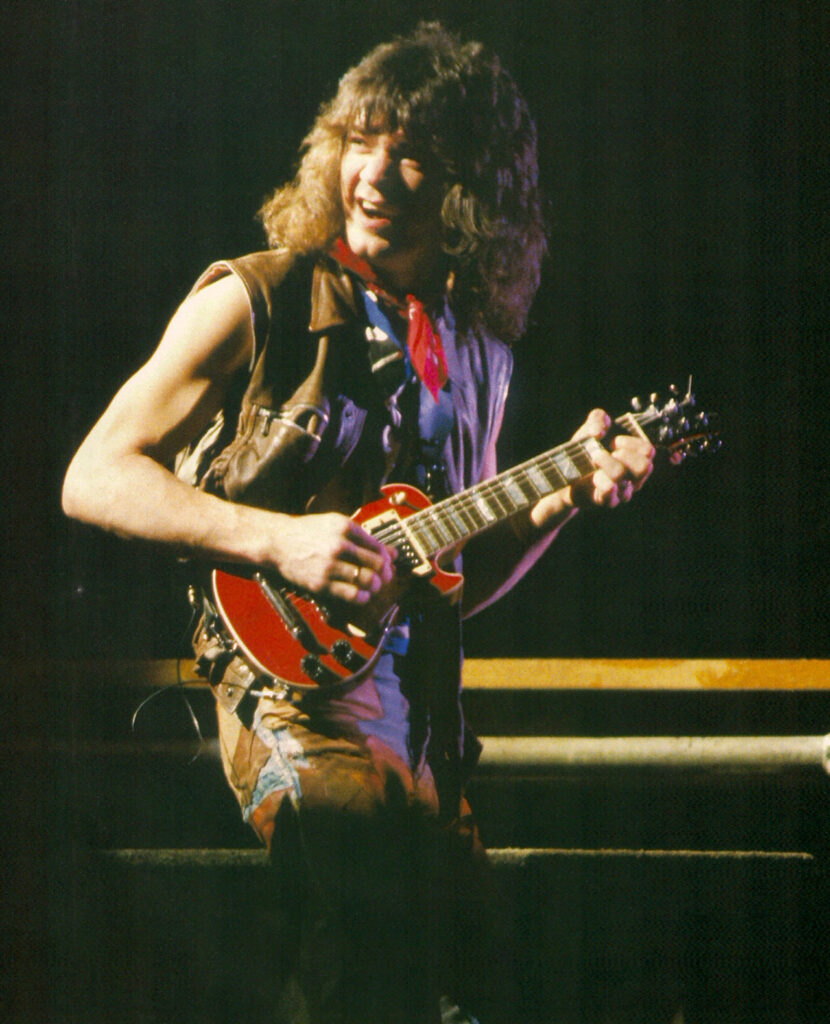

David Petschulat, a Nashville luthier, built miniature Les Paul clones that included a built-in amp/speaker circuit in addition to the standard 1/4″ jack. This could be toggled by a push/pull on the master volume. Ed met David while Van Halen was in Nashville on August 30, 1981 in support of their their ‘WDFA’ tour. Ed was quite impressed with the guitar, and purchased it from David. He would play it on the tour bus between shows, eventually writing the music to ‘Little Guitars’ on it. The song would be recorded in early 1982 for that year’s ‘Diver Down’ album, and Ed brought it on the 1982 tour in order to play the song live. Ed then commissioned David to built a second one out of a thicker body, and with no built-in amp speaker, in hopes that he could achieve a more refined live tone out of it. This was likely completed in 1983 and delivered to Ed, as it is first seen at the start of the 1984 tour. This second mini Les Paul – a wine red version with the aforementioned attributes – did not last for very long and Ed returned to using the original live for the remainder of the 1984 tour.

David supposedly also made the very first fine tuning tremolo, which can be read more about here.

Here is the story in David’s own words:

“I made Eddie’s first locking vibrato with fine tuners and sold it to him August 30, 1981 in the green room at the Municipal Auditorium in Nashville. I’d hunted him down in vacant downtown Nashville (it was Sunday everything closed) and pitched him my mini Less Paul guitar – he loved it on the spot and we went to the auditorium to follow through on the sales etc.

There in green room he contracted a second guitar – the wine red mini – and tried on and tested my wild lightening bolt guitar which had my vibrato on it. He didn’t so much like the lightening bolt but liked the fine tuners. He told me Floyd had been intending to make him one with fine tuners, but Floyd had been in a car wreck and badly hurt his back and had done nothing for months. Ed asked me to make one, and he gave me one of his own older Floyds at my suggestion so that I could make it faster and easier and we’d know it would fit on his guitars.

I took it and reworked it – which was REALLY difficult since Floyds are very hard on the rockwell scale – really hard. I sent it to him in March of 1982. I then wrote out a business plan and asked him to back me perfecting the design and the two of us getting it manufactured by a company. I did that all on notebook paper, hand written. It was very high-school kid looking. I got no reply. When I finally called his office to ask if he got the business plan, his staffer, Karen Valdez, asked me if I knew that the band had written a song using my mini Les Paul(s) – I said no – she said they even named the song Little Guitars. That was pretty cool. Yet I was flustered about him not following up on the vibrato potential..

I print up business cards and decide to pursue it myself – I go to the NAMM show in Atlanta since it’s 4 hour drive – I go to Allparts. No interest. WD Pickups and parts. No interest. A buddy tells me I better go to Kramer. I walked up and started to boil inside (and maybe a little outside). I look at a big poster of Ed holding a Kramer with some vibrato on it. Dennis Berardi walks up and starts to tell me with pride what they’ve done. I say something like “I find this all very interesting” no doubt with steam coming from ears. Ed walks up and says “aw, Dave, it’s not what you think.” He’d been approached by Rockinger, I presume through Kramer/Dennis.

With much hindsight it doesn’t bug me – I get it real well – Floyd’s recovering from accident, I’m a kid with a crude but working idea, Rockinger has a full-fledged product ready to sell – so that’s what they went with. Out of all of that, Floyd had the best design, hands down, but I like knowing I was a few months ahead of him in the early running. If patent law then was what it is now, I’d have gotten the document – but back then it was who invented first, not who applied first. And according to a napkin signed by a girlfriend, he edged me out of that possibility.”

Visit RIVET PICKUPS .

Below is information from David’s April 2021 Newsletter.

Can you believe a bomb exploded recently in downtown Nashville? It seems like “forever ago”, but that was just this past Christmas morning at 6:30am while you were probably still asleep. I remember sometime that morning, after a few cups of coffee, seeing the news. A local reporter described it and showed the surveillance cam footage with a creepy mechanical voice echoing “If you can hear this message, evacuate now…”, then ka-WHAM! – a white flash and debris dropping in flames on the city street. Holy cow! That happened right here in Nashville, Music City, USA.

The location looked familiar – I knew that part of town, but I couldn’t quite lock in on which street it was, or near which corner. Eventually the reporting got specific: it was on Second Avenue. I used to work on Second Avenue.

If you went to the location where that explosion happened and placed a ball in the street and let it go, it would in all likelihood roll a short ways downhill and gently come to rest near the door of what used to be the coolest guitar shop in America – probably the world – The Old Time Picking Parlor in downtown Nashville. I’m not even close to kidding you about how cool it was, and amazingly nobody has ever told the final chapter of its story before, but I’m going to tell it to you now.

First off, a bit of background for those of you who have not heard of The Old Time Picking Parlor. It has an incredibly famous history that has been cited in scads of magazine articles and a few books, been talked about in interviews with musicians, and has – of all things – appeared in what’s considered by many to be one of the greatest motion pictures of all time, Robert Altman’s “Nashville” – five Academy Award nominations and eleven Golden Globe nominations – to this day the most nominated film ever. Why all of this over a music store? It’s not just a coincidence that Altman chose The Picking Parlor (as most folks called it for short); he chose it because it represented a significant perspective on Nashville and Nashville’s music scene which defined the city. The Picking Parlor was the quintessential hang out. By day it was a musical instrument store and repair shop; by night it was a poppin’ night club featuring some of the greatest names in bluegrass, country, folk, rockabilly, and to some extent rock and roll music. Having music played at night in a night club is no surprise, but key to The Picking Parlor’s legacy is that all the same cats would come down to the store during the day – to get their instruments repaired or “tweaked” – and they’d stay for hours while it was being worked on, passing the time by nabbing instruments down from display on the walls of the store, and picking. Somebody else would show up and follow suit, and before you know it they’d be jamming and having a blast. Others might join in. Some shoppers would stop to listen. Word spread that it was a happening place and its influence spread from country legends that you rock and rollers may not be so familiar with, all the way to luminaries you know and love: Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Elvis Presley. EVERYBODY into lutherie in the 1970’s knew about The Old Time Picking Parlor. It was famous, it was wild, it was wooly, it was raw, it was downright exquisite. I’ll try to tell you more about those things in some detail someday, but as I turn towards how I stumbled into this scene, suffice it to say the place was like no place on earth for guitars and guitar music. Bar none.

Did I know any of the above when I sought out The Picking Parlor? Uh, no. None of it. Didn’t know, and frankly, didn’t care to know. I was a 21 year old suburban kid studying guitar in college because it was the only way I could trick my parents into supporting me while I chased after rock and roll. I think they figured I might become a high school music teacher or something. They had no idea that I instead wanted to stand in front of a blaring Marshall amp pumping vacuum tube squashed power chords from a stage. God bless us all for what we don’t know, right? Ironically, what I didn’t know at the time was that while I wished I had more of a knack for playing, I had a heck of a knack for messing with musical instruments. To find The Picking Parlor I looked up “Musical Instrument Repair” in the Yellow Pages phone book. I’d started making my own guitar but didn’t have a clue how to put in the frets. I bought a fingerboard at Gruhn Guitars but they were too busy to slot it. I took it to Sho~Bud, down the street – they were no help. Next on the list was The Picking Parlor. I called ahead and the man on the phone, the fabulous Coley Coleman, said to come on down and they’d fix me up. They really did, and it will take a few more newsletters to do that justice, but what you need to know now is that I went there for help with my frets and was immediately adopted by them – that very day Danny Ferrington raked a pile of trash off an unused workbench next to Jerry Jones and showed me what to do. We cut slots and installed frets, but before even that, Danny showed me how to saw shapes out of mother-of-pearl and we inlayed little stars on my fingerboard. I hardly recognized what had happened, but I’d found my tribe.

It was a fantastic place. The luthiers who worked there were stellar, and its history was rich. Ironically, I didn’t know it at the time, but The Picking Parlor was winding down when I arrived. The man who started it, Randy Wood, who worked on Elvis Presley’s guitar, had left the year before. Downtown Nashville had become a district of the worst sort of honkytonks (bad music and the smell of stale beer) and strip clubs and porno shops. The area stunk. The Picking Parlor was on a side street to all that in a neighborhood of old buildings constructed around the time of the American Civil War – interiors with exposed brick walls, high ceilings covered in stamped tin tiles, and occasional beams poking out here and there, and each building’s exterior having its own little bit of architectural flair. Sometime between the Civil War and the late 1970’s they had sadly turned into just dusty old warehouses. Nobody really wanted to do business down there. Suburban shoppers didn’t; it was too far away with little parking. Tourists didn’t; it was too lonely by day and dangerous at night. Thank goodness The Picking Parlor was around the corner and just far enough away from the squawking honkytonks of lower Broadway to avoid becoming one of them. Few people lived downtown back then; the area was nearly abandoned, and The Picking Parlor was in decline.

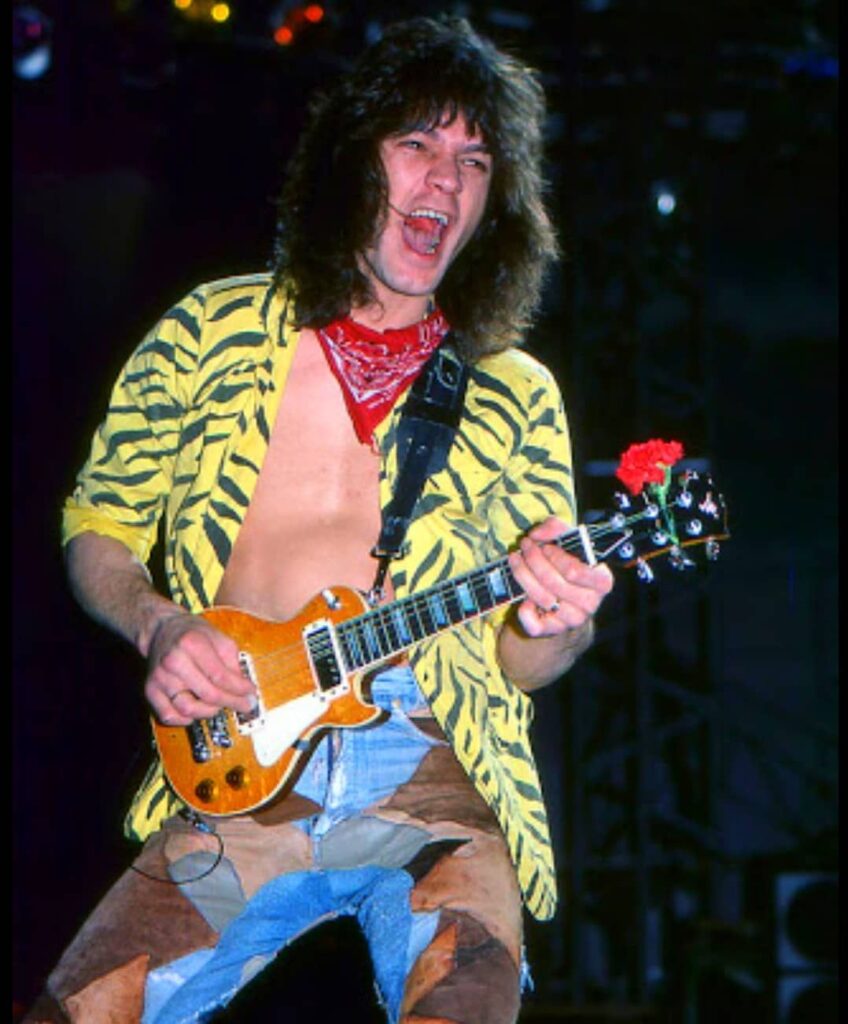

To me, though, it smelled like opportunity. I took in every guitar-making tip and trick that I saw somebody perform. They hired me pretty quickly with the deal being that I would learn and do repairs, and I could keep a percentage of the fees – but pretty quickly I started making more guitars. I did some repairs, but only enough to keep gas in my Honda motorcycle. I finished that first guitar, which is a monstrosity, but the second one I sold to Nancy Wilson of Heart. Then I sold one to Dave Hlubek of Molly Hatchet. Then Jackson Browne. Then Mick Jones of Foreigner. Howard Leese, Steve Morse. It was exciting. In the summer of 1981 I finished little #13 – a small Les Paul with a bird’s eye maple top, my “Flying P” logo, and a doggone tiny little amp and speaker stuffed inside of it. I took that guitar to a couple concerts that summer and pitched it to artists who maybe yawned or were amused, but nobody bought it. I toted it home on a visit to see my folks (see picture below at bottom). Then at summer’s end on a sunny afternoon in downtown Nashville, I went looking for and found Edward Van Halen. Because it was Sunday, nobody was around – nobody but Ed, Alex, and a manager – sitting on some steps and waiting on a ride to the auditorium they were play at that night. I walked up, opening the case as I approached. Ed instantly loved it. He bought it with cash from a briefcase his manager carried, and he contracted another one in a different color, which I made soon after, back at The Picking Parlor.

The Old Time Picking Parlor didn’t vanish after its famous founder, luthier Randy Wood, moved on, as the story is sometimes told. The other luthiers who had learned from Randy stuck around another year or two, and whether they knew it or not, managed to pass along something of the spirit of the place – its ambition and boldness – to younger guys like me still coming in. Eventually Coley Coleman, the owner after Randy, had to close The Picking Parlor down and move on. Coley went on to manage the recording studio owned by Cowboy Jack Clement (pal to young Elvis Presley, “discoverer” of Jerry Lee Lewis, and collaborator with Sam Phillips at Sun Records in Memphis). Over at Jack’s studio, Coley helped in the recording of U2’s “Rattle and Hum” album – and get this: a kid Coley had brought with him from The Picking Parlor, who had been the gopher working behind the counter selling strings and capos – once over at Jack’s studio, that kid winds up mixing part of U2’s album – and appears in U2’s movie about the album – and goes on to play the role of Jack Clement in the movie about Jerry Lee Lewis, “Great Balls of Fire!” –and goes on to partner with John Prine – and record with the likes of Dan Auerbach, Rick Rubin, and Johnny Cash. That would be engineer/producer/songwriter David R. Ferguson, one of a group of stubborn individuals remaining in Nashville today who stand as holdouts against the slicker side of Country Music. That’s not mere coincidence; The Picking Parlor laid the foundation for just these sorts of things.

In its final years, I made some very good friends among visitors to The Picking Parlor. Joe Glaser, luthier extraordinaire, lived at that time out in the sticks and would come in to town occasionally to stock up on fret wire and lacquer. Joe wanted to work at The Picking Parlor, too, not knowing how soon it would be closing for good. After it did, Joe let me finish my last guitar of that phase of my life at his shop in Leiper’s Fork, Tennessee, and Joe and I were close for years, developing a patent together (an adjustable fret system), and having several other escapades. On another of those final days, Coley comes back into the woodworking shop and tells me there’s a kid out front looking for me. That kid turned out to be Scott Borchetta who was new to town and sought me out having seen a blurb about my instruments and my then band in a trade magazine – Scott wanted to play bass. We joined up eventually. Scott was a rocket and went on to, among many things, sign Taylor Swift as a new artist on his young record label, Big Machine Records. Holy cow.

I’ve since lost touch with many from The Picking Parlor, but there were a bunch of quirky and wonderful folks there – the place attracted people like that – all of them pioneering something that fascinated them, or chasing something they loved. All of us were ambitious, but jealousies didn’t eat us alive – we got along pretty well. Randy Wood deserves plenty for setting the tone of the place to begin with, but I tip my hat to Coley Coleman, the man who kept such a rich and enchanted space going in its final years. I very much appreciated the whole experience, and I miss it.

So cool places encourage cool things. If you really dig something and there’s a crowd of people somewhere doing that thing – go there and introduce yourself. Grab a broom and sweep up; find a way to make yourself useful. Have fun, learn what you can, and get after it!

And now you know a few facts that not many folks know, except for me and you. I hope you’ll stay tuned in for more, and please, feel free to reach out to me with comments on my fresh new Facebook page for this project at https://www.facebook.com/petschulatguitars